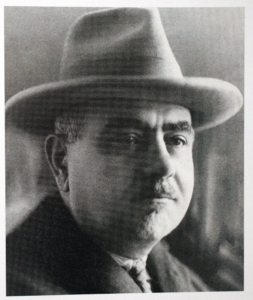

Abraham Giulkhandanian [1875–1946]

Born in Vagharshabad, Ejmiatzin, Giulkhandanian studied at the Gevorgian Seminary and later in Russia at the Yaroslavl Law School. He joined the ARF in 1894, and in 1898 went to Baku on business, remaining there for many years, devoting himself to ARF work.

Giulkhandanian became a member of the ARF Central Committee of Baku in 1902, continuing uninterrupted in that capacity until 1908. During that period, he established close ties between the ARF and Armenian oil well laborers in Baku, earning the respect of Armenians from all classes of society as well as non-Armenians.

An active leader in Baku during the Armeno-Tatar clashes of 1905–1906, he also led the Armenian defense in the Gandzak province (present-day Gyanja, in Azerbaijan).

In 1908, he became a member of the ARF’s Eastern Bureau and helped coordinate ARF activities throughout the Caucasus. He was arrested in April 1910, during anti-ARF persecutions headed by government prosecutor Prince Leizhin, and was not freed until 1912. He moved to Yerevan after his release.

In 1914–15, he became a member of the organizing committee of the Armenian Volunteer Movement. In 1918, he returned to Baku, where, with Rostom and other leaders, he helped conduct the heroic defense of the town.

Giulkhandanian served as a member of parliament independent Armenia, later becoming Minister of Justice in Aleksandr Khatisian’s cabinet, and subsequently Minister of the Interior. He was also part of Khatisian’s delegation that signed the Treaty of Alexandropol with the Bolsheviks in December 1920.

After the Sovietization of Armenia, Giulkhandanian fled to Romania. He eventually settled in Paris as a member of the ARF Bureau, taking charge of organizing the party archives.

An active writer for the rest of his life, Giulkhandanian published numerous books, articles, and memoirs regarding the Caucasus, the Armeno-Tatar conflict, Armenian revolutionary women, and ARF history.

During World War II, he was vice-president of the Armenian National Council in Berlin, and took part in the delegation that negotiated with Germany to form an Armenian regiment in the Caucasus composed of captured Armenian POWs.

He died in France. He was 71.

Immediately after the truce [in February, 1905], unprecedented meetings took place in Baku.

It was the first time in the history of the Caucasus that without any permission, without police participation, the people of Baku, irrespective of sect or nationality—Armenian, Jew, Russian, Tatar, and others—gathered together, three to four thousand strong, analyzed the events, criticized the government, and expressed their disgust while protesting the crimes that had been committed.

The meetings took place in the large hall of the citizens’ club, as well as in other halls in the oil-producing area of the city. They lasted over two weeks. They served two purposes: (a) to bring out the details of the crimes and to find the criminals; and (b) to expose the base, prevocational role played by the authorities in Baku.

The revolutionary parties of Baku and Russia had never had such an appropriate occasion to disseminate their ideas, and they used this occasion to the utmost. Thousands of citizens gathered together, heard about the unprincipled activities of the government and the inept authorities of Baku, and descriptions of how it had provided weapons to the Tatar murderers. Serious disclosures were being made, especially about Prince Nakashidze, who, during the conflict [between Tatars and Armenians], instead of trying to restore order, had shamelessly and openly encouraged the Tatar criminals.

All the revolutionary parties, which until that moment had operated undercover, in those days lay aside all secrecy and came into the open in the name of their parties, formulated resolutions, and demanded that all those responsible be put on public trial.

The police had totally lost bearings and didn’t know what to do. Diminsky, the police chief of the city, immediately after the events of February, had presented his resignation, and a few days later left Baku in haste. Khamitsky, the chief of police of the oil-producing area, as well as his second-in-command, ran away so quickly right after the ceasefire that they did not have time to pass their responsibilities on to their successors. As for the higher-ups, the governor and his aide, they did not dare interfere with the public meetings, perhaps because they felt guilty.

Was it the fourth or the fifth day, that a group of policemen closed the doors of the hall and tried to prevent the public gathering? But the meeting participants were so enraged that in mere seconds they scattered the police, smashed the locked doors, and, invading the hall, began their usual meeting.

The meetings ended with appropriate resolutions that were printed, and thousands of copies were distributed not only in Baku but practically all the cities of Russia, as well as overseas.

From Hay-Tatarakan Endharumnere

(The Armeno-Tatar Clashes), 1933