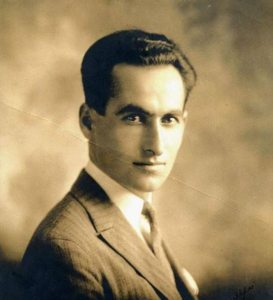

Soghomon Tehlirian [1897–1960]

Tehlirian was born in the village of Nerkin Bagarich, in the Erzurum region, and grew up in nearby Erzincan (Yerznga). He began his education at an Evangelical school in Erzincan, then attended the Ketronakan School of Constantinople. He began his higher education in engineering at a German university but returned to Erzincan when the First World War broke out.

In June 1915, during the deportation of Erzincan Armenians, Tehlirian witnessed the murder of his mother and brother, along with the rape and murder of his three sisters. He was struck on the head and left for dead. He survived and escaped to Tiflis, where he joined the ARF.

He participated in volunteer units commanded by General Antranig and also took part in the Volunteer regiment commanded by Sebouh.

In 1921 he was assigned to the ARF’s Operation Nemesis, which sought to punish Turkish officials guilty of organizing and carrying out the Armenian Genocide.

Tehlirian’s main target was Talaat Pasha, one of the triumvirate of Young Turk leaders who had ruled in the last days of the Ottoman Empire; he was a former minister of the interior and a grand vizier (prime minister). Talaat was killed by Tehlirian with a single bullet on the morning of March 15, 1921, in Berlin, in broad daylight. Tehlirian did not flee the scene and was immediately arrested.

He was tried for murder but was exonerated by the German court. His trial became a highly sensational event, examining not only Tehlirian’s guilt but also that of Talaat Pasha for the Armenian deportations and mass killings.

The trial influenced Polish lawyer Raphael Lemkin, who was later to coin the term “genocide.” He reflected on the trial, “Why is a man punished when he kills another man? Why is the killing of a million a lesser crime than the killing of a single individual?”

After the assassination, Tehlirian moved to Serbia and married Anahit Tatikian, who was also from Erzincan. The couple moved to Belgium and lived there until 1945, when they moved to San Francisco.

Tehlirian died in 1960 and is buried at the Ararat Cemetery in Fresno, California.

This is how Tehlirian himself describes that moment forever ingrained in Armenian history, the assassination of Talaat:

I awoke in the morning earlier than usual; the sun’s rays had already reached the window of the building across the street. I had just finished my tea and wanted to move the armchair to the window when suddenly I saw Talaat on the balcony of the building. I froze. Was it him? Yes…. He moved forward a step or two, carefully examined the sidewalk, first up, then down, and hung his head, who knows under the weight of what sort of thoughts. Apparently, his life wasn’t tranquil after the boundless crime he had committed. In any event, even though five or six years had passed, fear was ever- present for him. He bore on his wide shoulders two public death sentences: The Constantinople War Tribunal’s and the Armenian Revolutionary Federation’s. The first probably held moral significance for him: Instead of commending him for his great “patriotic” work, in his own land his fellow countrymen had condemned him to death as a common criminal. But time could resolve that “misunderstanding,” and future generations would understand the value of his work, if… if only there weren’t the death sentence of the Dashnaktsoutiun. All the same, he had been unable to eradicate all the leaders of that party. But who had remained from among his acquaintances? One person, for a fact: Garegin Pastermajian. Did he, I wonder, remember that last conversation with him…? Like a lever he lifted his thick arm, rubbed his forehead with his hand, and went in. I looked at my watch; it was 10 o’clock, his usual time for going to Uhland. I placed my weapon on me, ready to go out. Suddenly, he appeared by the door and began to descend, heavily, like an elephant. When I got outside onto the street, he was already heading toward Uhland on the opposite sidewalk. Cool-headed judgment was telling me that he wouldn’t be able to get away this time, but emotion was stirring up a tempest in me, telling me in multiple tongues, “Run, get to him, cross to the other sidewalk, and diagonally, from behind, at his back, his head, hurry, cross the street…” I stepped off the sidewalk to get behind him, but suddenly something drove me back. The thing that had clearly been confirmed a thousand times seemed, at that moment, suspect: Was it truly him…? “Get across from him, confront him, face to face, hurry, hurry, hurry, run!” I matched his position on the opposite sidewalk and with hurried steps passed him, moving far ahead; I crossed over to the same sidewalk he was on and reversed direction. We were nearing each other. He was moving as if on a stroll, carelessly swinging his walking stick. When only a short distance separated us, a surprising tranquility came over my entire being. As we were about to meet, he looked directly at me; the shudder of death flickered in his eyes. His last step stopped short; he turned slightly to flee, but in a single motion I pulled out my gun and fired a shot at his head…. Talaat seemed to stiffen from the blow, and his powerful body for a second became rigidly tall, unsteady, then like the sawed off trunk of an oak fell with a thud, face forward…. I never could have imagined that the monster would be laid low so easily. For a moment I had the urge to empty all my bullets into his torso, but instead of firing I threw away my handgun. The thick, black blood immediately pooled around Talaat’s head, as if oil were spilling forth from a broken pot…. I was enveloped by an internal satisfaction of spirit the likes of which I’d never experienced before. The constant nightmare that had perpetually settled on me, heavy like lead, seemed suddenly to have lifted. Everything had changed, it seemed; my fettered soul was soaring, free, far and wide; as if liberated from a state of being, my thoughts were circulating in all the known corners of the world.

From “Soghomon Tehliran: Recollections,” Vahan Minakhorian, Houssaper, Cairo, 1956