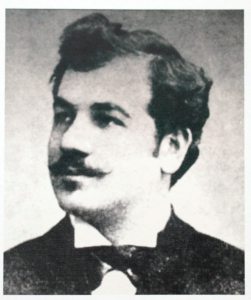

Armen Garo [1872–1923]

Born in Garin (Erzurum), Armen Garo graduated from the Sanasarian School there and attended the School of Agronomy in Nancy, France, in 1894.

Strongly attracted to the Armenian revolutionary movement, with a few friends he went to Geneva (Droshak) in 1895 to join the ARF. Soon thereafter he was sent to Egypt, Cyprus, then Constantinople, where he played a leading role in the seizure of the Ottoman Bank on August 14, 1896.

He and Hrach Tiryakian led negotiations with European ambassadors to end the Armenian massacres unleashed by the Sultan and to ensure the safe passage of the Armenian revolutionaries who had captured the Ottoman Bank.

He returned to Switzerland and resumed his studies, graduating in 1900 with a PhD in chemistry. In 1898, the Second World Congress of the ARF elected him a member of its Western Bureau.

In 1901 he settled in Tiflis. There, he led the defense of the mostly Armenian-populated city during the Armeno-Tatar (Azeri) confrontations of 1905–1906.

After the proclamation of the Ottoman Constitution in 1908, Armen Garo was elected a member of the Ottoman Parliament in 1909. He settled in Constantinople, then Garin.

In the autumn of 1914, he returned to the Caucasus. There, he played an important role in organizing the Armenian Volunteer Movement as General Dro’s associate and was appointed deputy commander of the Second Regiment.

After the independence of Armenia in 1918, he was appointed a member of the Armenian National Delegation at the Paris peace talks, and then ambassador of the Armenian Republic in Washington, DC, from 1919 to 1921.

He played a leading role in the planning and implementation of the ARF’s Operation Nemesis, the plan to assassinate Turkish leaders responsible for the Armenian Genocide. He died in Geneva in March, 1923. He was 51 years old.

We are in the bank. The time is approximately 1:30. The door is half-open. Standing directly across from the door, we are firing— Misak of Moush, Rouben, Mkhitar, and I on one side, and three comrades on the other. The smoke from the handguns has already filled the lobby; we can see nothing through the door; only the constant roar of rifles lets us know that there are large numbers of troops outside….

As soon as we turned again toward the door… a terrible explosion. It was Misak of Moush. While taking the bombs from his belt, he was shot and wounded in the leg and released a bomb. The scene was terrifying; he was lying on the stone floor, his left forearm shattered, his right arm torn to bits, hanging from his shoulder by a few strands of muscle, his face bloody, his clothes ripped apart….

We heard from outside: “Men, go in, go in,” and saw the tips of bayonets shining through the smoke…. The rounds fired from six or seven handguns drove back the bayonets… [and] the explosion of five bombs cleared the street for a while.

As Mkhitar and I, carrying more bombs, turned toward the window, Misak, with his frightful appearance, on his knees, neck bent, popped up in front of us: “Baron jan, kiz ghurban, meg ghurshun esdeghits” (Sir, please, one bullet, aimed here) he said, pointing toward his breast with the remainder of his right arm. I began to shake with my whole being. I can’t say for certain what I felt at that moment. I remember only that I put the wooden part of my handgun in my mouth, bit on it with all my strength, and looked away. Again he came in front of me, dragging his bloody leg on the floor.He repeated his request… his voice, his appearance demoralized me completely. To reject him was unmerciful; each second brought terrible torture for him…. I don’t know why I didn’t empty my gun into his tortured chest, and I turned to Mkhitar: “Mkhitar jan, free the poor boy.” Misak immediately turned his bloodied face toward him and said, “Mkhitar jan, kiz madagh, meg ghurshun.” Mkhitar, completely pale, with shaking hand pointed the handgun toward his chest…. Misak, a trace of satisfaction on his face, pulled hack his dismembered arms as if to make his comrade’s task easier. Eyes filled with tears, Mkhitar looked at me, “No, I can’t,” and turning to Misak, weeping, said, “Misak jan, go stand in front of that second window, and one of the bullets from the soldiers will take you.”…A few seconds later Misak was kneeling in front of the window, his head and a part of his chest sticking out the window…. He yelled in a loud voice and poured out a string of curses at the soldiers. Fifteen minutes passed, and despite… the hundreds of bullets flying by him, none killed him.

Suddenly he stopped his shouting and turned toward us, “Boys, get ready, bashibozuk [irregulars] are coming.”… When the mob attacked the door, six of us on the first floor… and [five] comrades from the roof sent a downpour of bombs…. The heart-wrenching screams of the wounded, the crash of window glass from the building across the street, and the dynamite’s blue smoke rising toward the sky shook me for a moment: We were dealing with human lives… Who gave us this right… But why did they start it… Who were the ones, months before, who caused rivers of blood to flow…. I looked out the window… bodies… the remainder of the mob fleeing in terror….

In a moment of terrible silence, I hear Misak. I turn to my right. His bloodied arms hanging like rags out the window, waving them at the fleeing mob, a horrifying smile on his face, he cursed with his already hoarse, half-dead voice.

Oh, that smile of his…

If one day in this struggle for survival the time comes for our afflicted Armenian nation to die, to disappear from the face of the earth, if it does so without that last smile of Misak of Moush… a thousand pities for the blood it has shed.

From Droshak, 1900