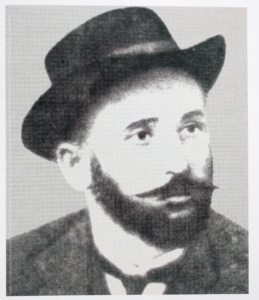

Garegin Khazhak [1867–1915]

Born Garegin Chakalian in Alexandropol (Giumri, later Leninakan), Khazhak graduated from the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Geneva with a degree in sociology.

In 1894, he returned to Geneva from Baku, where he had joined the ranks of the ARF, and began to work for Droshak, the central party organ.

In 1895 he was sent on an organizing mission to the Balkans, where he soon became one of the leading pioneers of the ARF. Later (1897–98) he was sent on a similar mission to Smyrna, then Egypt.

From 1898 to 1903 he was a member of the ARF’s Responsible Body for Constantinople.

Returning to the Transcaucasus in 1903, he taught at the Nersisian College in Ejmiatzin and contributed to Mshak in Tiflis. From 1906 to 1911, in Tiflis, he was a member of the editorial team of Harach and Alik with Avetis Aharonian and Yeghishe Topjian.

He settled in Constantinople in 1911–1912 and became the director of the national school in the Samatia district, working for the newspaper Azatamart at the same time.

One of the most brilliant representatives of the Dashnaktsakan intelligentsia, Khazhak was also among the first victims of the Armenian Genocide, in 1915. He was 48 years old.

My dear Shoushanik, sweet companion of my life:

Today I can write with assurance that they are taking us to Tigranakert [Diyarbekir] to hand us over to the military court, under the suspicion that we want to start an insurrection in the land. And that means they are taking us there to hang.

Therefore, my beautiful companion, when by some miracle this letter reaches you, I will have ceased to exist. My dearest, carry out my last request:

1. Take the children and leave this accursed and immoral country; settle in our old home and dedicate yourself to the education of our children.

2. Keep this piece of paper, and when the children become of age give it to them; let them read it and follow their father’s footsteps.

I will soon have lived 48 years, but I have not yet lived 48 days with moments of rest; the damned fate of the Armenian people has pursued me, and it seems it has focused on my comrades and me. To live like this is bitter, very bitter, and to die like this is especially bitter. I am angry but not despondent. Be certain that when facing the gallows, I will have two pictures before my eyes: first, the suffering of my people; second, yours, my Nunu’s, my Alo’s and, alas my third child’s. Will I cry or smile, I don’t know… If only, before I hang, my heart, which has begun to throb so loudly, would burst… How terrifying it is not to see the birth of one’s child and to be hanged… and to be hanged so treacherously like this, without any just cause, merely by suspicion. My beautiful Shoushanik, when my children are grown, give them these few lines… let them dedicate themselves to [assuaging] the pain of their people and nation.

There is no tear in my eyes, perhaps because, as a human being, I still harbor hopes that I will live…. Although I have not participated in any practical work in Turkey, I will nevertheless hang, because I am a known Dashnaktsakan….

Goodbye by beautiful companion, goodbye by angels Nunush and Alo, and goodbye my third and unknown child, whose birth into the world I will not see. If only we would be the last victims sacrificed on the altar of the Armenian people; if only with our blood this wretched nation would finally find its rest. Goodbye. I pour all my soul in my kiss that I place on this piece of paper…. It is as if the prophecy my mother made in 1892, “You will die in a dark jail,” is coming true. God, how bitter the thought of dying far away from loved ones. My kisses, again and again, to all of you. Let our children walk the path I traveled, a bitter but noble path.

Your Khazhak

July 4, 1915