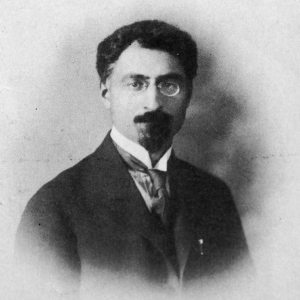

Reuben Darbinian [1883–1968]

Born in Akhalkalak, Darbinian was taken to Ekaterinodar (present-day Krasnodar) as a child by his parents. He was educated there and in Tiflis. In 1903 he attended Moscow University, and later traveled to Germany to further his studies.

He joined the ARF in the early 1900s, and by 1906 he had become chairperson of its North Caucasus Central Committee. Due to his revolutionary activities, he was forced by Tsarist authorities to flee in 1909.

Moving to Constantinople, Darbinian continued his activities, becoming editor of the ARF organ Azatamart. In 1914, he returned to Tiflis, and from there went on to Baku as editor of various ARF papers.

During the “Baku Commune” of 1918, Darbinian traveled to Moscow with Simon Hakobian to secure Bolshevik aid against the Turkish forces besieging Baku. In Moscow, however, he was met with hostility on the part of Soviet authorities.

In 1919, Darbinian moved on to Yerevan, where he became Minister of Justice in the government of Aleksandr Khatisian. He also served for a time as editor of the party organ Harach.

When the Bolsheviks occupied Armenia in late 1920, Darbinian attempted to flee but was apprehended and jailed. He was freed by the popular revolt of February 1921, and during the ensuing months he remained in Armenia as editor of Azat Hayastan. He escaped the return of the Bolsheviks by going to Tabriz (Iran) and from there to the West.

Darbinian eventually settled in Boston, where he assumed editorship of Hairenik in March 1922. During his long tenure, Darbinian became known for cultivating the talents of many writers and cultural figures, and he oversaw the founding and enlargement of publications that served to supplement the Hairenik daily: the English-language Hairenik Weekly, the scholarly and literary Armenian Review, and the Hairenik Monthly, which was notable for publishing the memoirs of many early Dashnak leaders.

Darbinian was also known for his strong, uncompromising anti-Communist stance—a view he held throughout his middle and later years.

He died in Boston. He was 85.

When, after a three-month illness I once again stepped onto the streets of Moscow [1919], I was truly terrified. It seemed the entire city had been subjected to a terrible pogrom. All the shops were closed. Their shelves were emptied. Sometimes only a few pieces of cardboard, leftover goods, and piles of dirt were the only remnants of a once-plentiful, prosperous store. The shattered furniture and windows left no doubt that the hands of vandals had been the cause of this wholesale destruction.

I was sick abed when I read the Soviet decrees about the nationalization of business. I never dreamed that these decrees could in reality have wrought such havoc; to complete the picture, the Bolsheviks had removed all signs and marquees of the stores, without which the city looked completely transfigured and desolate…

Not only in the evenings or at night were the streets empty, but even in the daytime, with the exception of those hours when government clerks or the workers were on their way to, or returning from, their work. After 4 PM (which in reality was 1 PM, because the Bolsheviks, by a crazy whim, had advanced the clock three hours), all the streets of Moscow were empty. Only at times casual passersby stalked the streets like ghosts. Only one thing was stamped on all faces: Terror! All seemed to be fleeing from something, all were in haste, almost running. Men or women were seen, carrying on their shoulders or sometimes on small carts, loaded bags or packages filled with flour, bread, potatoes, or blocks of wood for fuel. It seemed men had no other occupation but to seek something to eat or burn.

Only after long weeks did the Soviet government open a few stores, where, according to public announcement, goods could be procured with special rationing cards. These cards were of four class es: (1) The workers, the most privileged class, whose allowance was more than all other classes’; (2) ranking Soviet functionaries; (3) the non-ranking public servants; and last, (4) all the remainder, namely, the bourgeoisie and the nobility. With the merging of the first two classes, however, soon the public was divided into three classes. In other words, these very same Bolsheviks who were loudest in their condemnation of the classes, now created new classes even on a simple matter as the dispensation of life’s necessities.

From “A Mission to Moscow,” Memoirs of Reuben Darbinian, 1948, the Armenian Review, Vol. 1