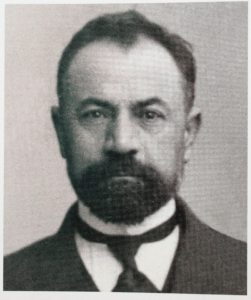

Stepan Zorian (Rostom) [1867–1919]

Born in the village of Tsghna, in Goghtn, Nakhijevan, Rostom completed his secondary education in Tiflis, Georgia.

In 1889, he enrolled in the Moscow Institute of Agronomy but was eventually expelled for being a revolutionary. He became a founding member of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, and from 1891 onward, first in Tiflis then in Tavriz (Tabriz), Persia (Iran), Rostom became one of the most active figures of the Dashnaktsoutiun.

He was present at the First World Congress of the ARF, and with the input of Kristapor Mikayelian and Simon Zavarian he wrote the introduction (on Ideology) of the ARF’s Constitution. He then went to Geneva, where until 1895 he worked on Droshak, the ARF’s central organ.

In 1895, disguised as a samovar salesman, Rostom was in Karin/Garin (Erzurum), where established revolutionary student associations. He was later sent to Iran and the Caucasus on organizational missions. He subsequently returned to Geneva, remaining there until the Second World Congress of the ARF.

From 1898 onward he settled in Philippopolis (Plovdiv), Bulgaria, where he and his wife, Lisa Melik-Shahnazarian, established an Armenian school. While there, he became the architect of collaboration between the ARF and Macedonian revolutionaries.

Rostom returned to the Caucasus in 1902 and played a leading role in anti-Tsarist activities from 1903 to 1904, and in the Armeno- Tatar (Azeri) conflict of 1905–1906, defending Armenians throughout the Transcaucasus from Tatar atrocities.

He went to Persia to establish cooperation with Persian revolutionaries, assisting Iranian constitutional forces in their uprising against the Shah (1905–1907).

In 1907, the presence of Rostom at the Fourth World Congress was a decisive factor in the synthesis of left- and right-wing tendencies in the ARF.

After attending various congresses of the Socialist International, Rostom returned to Garin and remained there until the Eighth World Congress (1914). In 1915, he played a leading role in organizing the Armenian Volunteer Movement and the formation of the volunteer regiments attached to the Russian army. In 1918, Rostom was the central figure in the heroic defense of Baku against Ottoman Turkish forces that were attempting to occupy the oil-rich city.

He contracted either typhus or typhoid fever, and died in Tiflis in January 1919, at the age of 52, without having stepped foot in the newly independent Armenian republic.

Rostom’s thought leadership, implacable will, and relentless organizational activity left an indelible mark on the ARF and its mode of operation.

Each time that thanks to the selfless, constant, and unwavering activities of the revolutionary minority the revolutionary organization gains strength and influence, creates faith in the success of the work, and to a certain degree clears the way for the revolution—each time a commotion arises in the various segments of society. Along with the rising of the revolutionary spirit in the people, all sorts of opportunists, exploiters, usurers, snitches, even traitors—in a word, all manner of snakes that know how to amazingly adapt to conditions and profit from them—come to the fore as “revolutionaries” or sympathizers of the revolution.

Such people are insidious, especially at those moments when with overblown statements and pharisaic gestures they exploit the naiveté and ignorance of the masses. And they are unbearable, they are an affliction and a calamity for the revolutionary movement, when the revolution is confronted with a temporary setback and conditions become difficult for revolutionary workers. During such times, those abhorrent creatures quietly return to their lairs, and in an attempt to conceal their true colors, under the masks of “common sense,” “farsightedness,” and “love of the people,” they continue to toy with the people. Continuing to bear the titles of “revolutionary” or “patriot,” they become the most damaging obstacles to real revolutionary work. They are like garbage in large and small piles with various smells and colors strewn along the revolutionary path, polluting the environment.

Every revolutionary worker is compelled from time to time to leave his main work and concern himself with that garbage that falls in his path and impedes his progress. Willingly or unwillingly, from time to time he must take upon himself that repulsive task, despite knowing full well that with the first swing of broom those piles will be exposed, filling the air with their stench. Through that atmosphere of gossip, accusation, and intrigue the true revolutionary must continue toward his main purpose.

From “Vnasakar Tarrer” (Harmful Elements), Droshak,

May 1, 1896