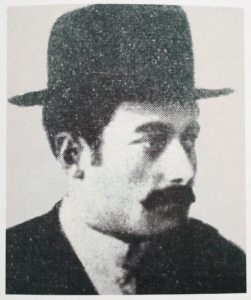

Rouben Ter Minasian [1882–1951]

Born in Akhalkalak (present-day Georgia) to parents who had migrated from Erzurum, Rouben studied at the Gevorgian Seminary in Ejmiatzin and then at the Lazarian College in Moscow. He then served as an officer in the Russian army.

As a young ARF organizer, he was molded into a Dashnaktsakan in the intense revolutionary activity of the “Kars Furnace” in 1903–04. He was dispatched to Van in 1905 as a plenipotentiary representative of the ARF.

He joined Aram Manoukian in Van, then operated in the Lernabar region (south of Lake Van), but after tactical differences with Vana Ishkhan he left for Sasoun to back up Kevork Chavoush in 1906. He stayed there until the proclamation of the Ottoman Constitution, having taken sole charge of the Dashnaktsakan fedayi forces in Sasoun after the death of Kevork Chavoush in May 1907.

He attended the Fifth ARF World Congress, in Varna, Bulgaria, in 1909 and then left for Geneva to resume his studies. Summoned to Moush in 1913, he later went to Sasoun and with his veteran fedayis led the heroic defense of Sasoun against regular Turkish forces and Kurdish irregulars in 1915. With a handful of men he broke through enemy lines and crossed into the Caucasus.

In 1917–18, he was a member of the Armenian National Council, based in Tiflis, and was elected to the parliament of Independent Armenia. He was elected to the ARF Bureau at the Ninth World Congress in Yerevan and remained a member of it virtually without interruption until his death.

He served as minister of war in the Bureau-government of Ohanjanian, playing a leading role in suppression of Bolshevik riots and the elimination of Turko-Tatar insurrections in Armenia.

After the Sovietization of Armenia, he went to Zangezour, then crossed into Iran, and eventually traveled to France, Egypt, and Lebanon, and finally settled in Paris.

The seven volumes of Rouben’s memoirs, Memoirs of an Armenian Revolutionary, are exceptionally valuable both as testimonies about men and events and as a storehouse of revolutionary ideas and analyses.

He died in Paris on November 29, 1950, at the age of 69.

At sunset the fedayis would rise to their feet, regardless of the darkness and the inclemency of the weather. Like the wolves they had to prefer the dark night. At such times the fedayi is more formidable to the enemy. The fedayi loves to travel on rainy or snowy nights.

When the fedayi is ready to take off, he embraces and kisses his comrades, they crack jokes, and the entire community’s men, women, and children bid them farewell with tearful eyes. The word used on such occasions is “Oughour,” which means “God be with you [good luck].” The fedayis respond by saying, “Shen Mnak,” which means, “May you be prosperous [be well].” Generally the villagers are forbidden to accompany the fedayis. On frequent occasions they appoint a villager to stand guard so that no one shall see in what direction the fedayis move.

After they leave the village, the fedayis themselves do not know where they are going. They stop at the outskirts of the village, waiting for the orders of the company commander, who alone known where they are going. The latter calls two fedayis who are his best scouts and whispers in their ear the direction he wants to take. The scouts instantly take their place at the head of the company, make a detour, and circle the whole village to confuse the villagers. The company follows the scouts at a distance of 50 to 100 paces, the company commander marching on their side or in the rear, always accompanied by two aides. The company follows the commander at a distance of ten paces. Two fedayis lag behind to act as rear guards.

On the march it is strictly forbidden to talk to one another; likewise, smoking or coughing are out. The rifles are sheathed with a cloth jacket to prevent glinting in the sunshine, or grating against the bandoliers or rocks. The careless fedayi is promptly brought back to his senses by the corporal’s or company commander’s solid fist on the nape of his neck, and the company resumes the trail…

The fedayis are good marchers, easily making a distance of 5 to 6 kilometers in one hour. Each night they cover a distance of 25 to 40 kilometers, the idea being the longer distance they leave behind, the better. They generally shun the villages on the road to prevent detection. They cross the rivers and streams with great care, never removing their clothes, in order to gain time. The bandolier is never taken off, even though at times the baggy trouser is shed. It is too risky to be separated from one’s weapons even for a moment.

After a march of three to four hours the fedayi is permitted to smoke a cigarette, provided he is careful to hide the light of his match. The night march must come to its end by daybreak when the company has reached its destination. Upon arrival the company does not enter the place at once but halts some distance away until the scouting is completed. Two fedayis enter the village and call at the home of the most reliable person. They explain the purpose of their call, and after taking stock of the situation, they return to the camp, accompanied by a villager who leads the company to their quarters, generally four to five homes best suited against surprise attack.

In the morning, when the village comes to life, no one knows about the visitors except the host families. By afternoon the word spreads and in the evening preparations are made for a public meeting and the order of business.

The fedayi does not rest immediately upon his arrival, but first is feted by the hosts. Then he retires into a dark corner of the stable or the barn. At daybreak one of them stands guard while the rest go to sleep on blankets, their rifles carefully tucked between their legs. It is strictly forbidden to take off the bandolier. Thus taking turns, they sleep into the afternoon.

From Memoirs of an Armenian Freedom Fighter, 1963, Hairenik Press, James G. Mandalian, translator