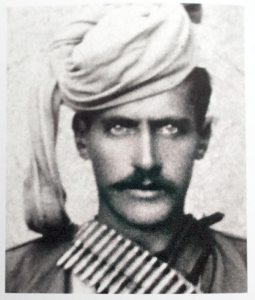

Sebouh [1872–1940]

Born in the village of Varzahan, in Papert (Bayburt), Western Armenia, Sebouh showed early aptitude as a craftsman. He received his secondary education in Trebizond.

He joined the Hnchak party in Constantinople in 1889 and participated in the 1892 demonstration at Kum-Kapu, protesting Ottoman oppression. Afterward, he left for the Crimea, then the Caucasus, where he joined the ARF in 1894. He became a party organizer in his hometown and took part in groups that transported arms to Western Armenia.

In 1903, Sebouh went to Sasoun and joined Torkom’s “Mrrik” group. He later became one of the leaders of the 1904 Sasoun rebellion. Seriously wounded in Sasoun, he remained in Akhlat for a time, then Vaspourakan (Van).

During the Armeno-Tatar conflict of 1905–1906, Sebouh fought in Nakhijevan. He also took part in the Iranian Constitutional Revolution (1905–1907). He attended the ARF’s Fourth World Congress in Vienna, in 1907.

After the proclamation of the Ottoman Constitution in 1908, the Ottoman authorities ceased to persecute former revolutionaries, and Sebouh returned to his birthplace, where he lived for a time.

In 1914–1915, Sebouh fought in the battles of Khoy and Dilman at the side of Antranig. Later, he was part of the Armeno-Russian forces that liberated Garin (Erzurum) in 1918. At the head of an ARF formation, he took part in the decisive battle of Sardarabad in 1918. He then went on to Baku to protect the Armenians under siege there and to defend the city against Ottoman forces.

After the independence of Armenia, Sebouh bore the rank of brigadier general in the Armenian Army. At the head of a special unit, in May 1920, he suppressed the Bolshevik insurrection in Shirak. He also fought in the Armeno-Turkish War of 1920.

After the Sovietization of Armenia, he left for the United States, where he died at the age of 68.

[In 1917–1918] the situation was sad and grim…. Where was that great military leader who enjoyed the sympathy of the people and could lead it?

There was no one. We had no one. If there was a military man whom we could call “great,” he was General Nazarbegov, who was sitting in Tiflis and did not want to come to this side [Western Armenia]. What is he thinking and why does he not come? No one knows. Perhaps he, with his authority and impartiality, could put an end to the Russian-Armenian vs. Turkish-Armenian problem. And if there was to be an improvement in our military situation, only Gen. Nazarbegov could accomplish it.

The greatest source of adversity and misfortune for us is this sectarian passion. The day that it ends, so will our misery; the Armenian people will be freed from the oppression of their own passions, as well as external enemies.

From Pages From My Memoirs, Hairenik Press, Boston, 1925